Last week, Democratic presidential candidate Beto O’Rourke told a CNN town hall that religious institutions—from colleges to churches—should lose their tax-exempt status for opposing same-sex marriage.

The same day, Elizabeth Warren, who leads the Democratic field, wrote that she would “use every legal tool we have to make sure that LGBTQ+ people can live free from discrimination,” including passing the Equality Act, refusing federal grants to organizations that oppose the hiring of practicing LGBTQ+ individuals, and limiting religious exemptions to faith-based colleges.

For Christian college presidents and boards, the language is alarming—but not entirely unexpected.

Five years ago, the Obama administration told schools to treat transgender students according to their preferred gender. Two years later, the administration explained that meant allowing transgender students to “participate in sex-segregated activities and access sex-segregated facilities consistent with their gender identity.”

“Most of us went to bed on election night [2016] thinking, I have to get up tomorrow and think about defending religious freedom,” Covenant College president Derek Halvorson said. “Then we woke up and said, ‘Oh my goodness. What happened? I don’t know what this means, but I think we’re getting a reprieve.’”

The reprieve was bigger than they could’ve imagined—President Trump appointed Calvin College graduate and school-choice advocate Betsy DeVos as his secretary of education.

Under her direction, the Obama letter instructions were rolled back. Then she announced a bill that would give federal income tax credits to those who contribute to private K-12 scholarship funds, proposed lifting any remaining restrictions on religious colleges’ ability to receive federal aid through programs like work-study, and began working to better define “religious mission” in the Higher Education Act, which could offer another line of protection against government regulations and potentially hostile accrediting bodies.

But at the Council for Christian Colleges and Universities (CCCU), “we’ve never relaxed our advocacy on these issues,” said CCCU president Shirley Hoogstra. “There’s been no backing up. In fact, [pressure to conform on same-sex issues] has been accelerating through culture.”

Over the last several years, Christian colleges have been running calculations on how they might survive without government funding. They’ve appointed committees to look into other options. They’ve joined accreditation commissions. And the CCCU has filed amicus briefs on religious freedom cases, worked with the Department of Education on regulations, and advocated for Fairness for All—drafted legislation that would add LGBTQ rights to federal civil-rights laws in exchange for religious exemptions.

Not everyone agrees Fairness for All is the way forward. The trouble is, there is no clear way forward.

“The concerns are very real,” said former CCCU board chair David Dockery, who finds Fairness for All “well-intentioned, but a less than satisfying option.”

“The issues potentially affect hiring rights, student life policies, funding, tax-exempt status, and accreditation,” he said. “It certainly keeps one up at night because there’s no obvious answer, no clear strategy.”

Nobody knows exactly what to do.

On the same day in March 1993, a Democratic senator and a Democratic representative introduced a bill bolstering religious freedom. The Religious Freedom Restoration Act (RFRA) said the government could only “burden a person’s exercise of religion” to advance a “compelling government interest”—and even then, it had to use the least restrictive way.

The bill was enormously popular, passing unanimously in the House of Representatives and missing only three votes in the Senate. Democratic president Bill Clinton signed it into law.

But united approval immediately began to erode. Four years later, the Supreme Court ruled that RFRA didn’t apply to states. Two states had already passed their own versions, and 19 more would join them. But by the time Indiana got around to it in 2015, the criticism was so loud that a follow-up amendment was quickly passed. When Georgia tried in 2016, governor Nathan Deal vetoed it after multiple celebrities, the National Football League, and the Walt Disney Company threatened to pull operations from the state if it became law.

The issues potentially affect hiring rights, student life policies, funding, tax-exempt status, and accreditation.

The biggest objection was that religious liberty would step on gay rights. Cultural support was rising rapidly for same-sex marriage (from 35 percent in 1999 to 60 percent in 2015), equal access to employment (83 percent in 1999 to 93 percent in 2019), and the legal right to adopt (49 percent in 2003 to 63 percent in 2014).

Increasingly, religion was looking more like the oppressor than the victim. Why should a Christian baker or photographer be able to turn down same-sex couples looking for wedding services? Why should a church get to limit its building to heterosexual wedding ceremonies? Why should a college get to limit its hiring to those who believe in traditional marriage? Why couldn’t a university assign dorm rooms based on preferred gender identity?

These ideas are clashing in all three branches of the federal government—and Christian colleges are worried about every one.

This spring, the House of Representatives passed the Equality Act with no religious exceptions. In fact, it specifically noted that RFRA “shall not” be used as a defense. That means all colleges—and other faith-based organizations, from adoption agencies to homeless shelters to TGC—that want to impose sexual standards for employees or clients or students would be violating the law.

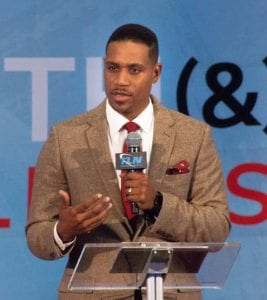

“Based on the Equality Act, SOGI [sexual orientation and gender identity] rights would override religious liberty,” AND Campaign founder and political strategist Justin Giboney said. “There would not be any exemptions for faith-based institutions. It’s really problematic.”

He’s right, for now. The Equality Act stalled in a Republican-controlled Senate, and it’s improbable that Democrats—now numbering 45, with two Independents who caucus with them—will gain the seats needed (60) to break a likely Republican filibuster and move the Act on to the White House.

“The worrisome scenario is one in which the Democrats hold the House, take the White House, take the Senate, and abolish the legislative filibuster,” said Greg Baylor, senior counsel for Alliance Defending Freedom’s and director of the Center for Religious Schools. “This scenario probably won’t unfold in 2020, but, if it did, the threat would be very serious.”

Just as concerning is the trio of cases in front of the Supreme Court this fall. Justices will decide whether sex discrimination in employment—prohibited by Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964—should be expanded to include sexual orientation and gender identity. (Should a boss be able to fire an employee for being openly homosexual? Should a funeral home owner be able to fire a director because he now identifies and dresses as a woman?)

Reframing “sex” as “sexual orientation and gender identity” and banning hiring practices based on both would “have consequences for religious institutions of higher education ranging far beyond employment requirements,” states an amicus brief submitted by the CCCU. “Student housing standards would face new pressure. Affiliated clinics and hospitals could be compelled to provide religiously objectionable medical procedures. A religious university’s tax-exempt status could be challenged or revoked. Accreditation agencies could rely on Title VII as justification to disregard a university’s religious mission.”

The court heard oral arguments this month and will probably issue an opinion next June. Five of the nine justices are generally conservative, and Chief Justice John Roberts asked directly about religious exemptions.

However, the discussions didn’t make it clear which way the decision would go.

“The justices appeared to be closely divided on the merits,” Becket Fund for Religious Liberty senior counsel Luke Goodrich said. “It is hard to predict the outcome.”

From the executive branch, the letters detailing how to comply with the law have been the most alarming. These instructions don’t need outside approval to take effect.

At the town hall forum, all of the Democratic presidential candidates signaled their support for LGBTQ rights over religious freedom—some more clearly than others. (“The right to religious freedom ends where religion is being used as an excuse to harm other people,” candidate Pete Buttigieg said.)

“The rhetoric of the candidates finally bared the teeth of a Democratic Party sold out to the most radical proposals of the LGBTQ movement,” wrote Al Mohler, president of The Southern Baptist Theological Seminary and TGC Council member. “[E]very candidate during CNN’s Equality Town Hall, in one way or another, unleashed a full broadside against the most essential quality and virtue of any government or civilization, namely, the freedom of the conscience.”

The way most Christian colleges have protected themselves—by asking for a religious exemption—has been, if uncomfortable, effective. No one has yet been denied a religious exemption from the Department of Education.

But asking for one can put you on public “hate lists,” get you an unwanted label, or cause local bodies to cut funding or partnerships.

And the language from Democratic presidential hopefuls has been anything but reassuring.

“This is a real problem in America and I will, number one, change the Trump administration’s guidance back to what the Obama administration’s guidance was that schools should allow people to use the bathrooms that conforms with their gender identity,” presidential candidate Cory Booker said at the town hall forum. “But we cannot stop there. . . . We must use our Department of Justice and the Department of Education’s civil rights division to go after schools that are denying people equal rights and equal protections.”

During the Trump reprieve, Christian colleges have been contending with LGBTQ issues closer to home.

In California, state senator Ricardo Lara proposed legislation that would cut off state funds from schools that asked faculty or students to adhere to certain codes of conduct—such as refraining from same-sex relationships or using only bathrooms that match their biological gender. The bill was amended, but Biola University president Barry Corey said “we spend a lot more time thinking about Sacramento than Washington.”

Other threats are even more localized. After Gordon College president Michael Lindsay asked the Obama administration to include a religious exemption in an executive order banning SOGI discrimination by federal contractors, his city kicked the college out of its management contract on the town hall. Gordon’s accreditation agency announced it would publicly review the school’s good standing. (Gordon kept its approval.) A local school district stopped letting Gordon students serve as mentors; years earlier, another school district began refusing Gordon’s student teachers because of the school’s stance on homosexual behavior.

In Minnesota, some larger mental health facilities won’t take Bethel University’s masters students in counseling because of the school’s stance on marriage.

“It would be a big hit if health care organizations stopped taking our nurses for clinicals, or social work agencies stopped partnering with our social work majors, or public schools stopped taking student teacher placements,” Bethel president and CCCU board chair Jay Barnes said. “Without Fairness for All, there is currently no strategy to get around that. That would be extremely difficult.”

Administrators also worry about the potential loss of reputation, Dockery said. “How do we navigate these challenges without appearing to be hateful or homophobic?”

“We’re meant to be part of an ecosystem,” Corey said. “If all of those connections to the ecosystem are cut off and our students don’t get hired or internships, or we don’t get vendors, or we lose accreditation—that’s the bigger issue.”

It can be paralyzing to think about all the ways Christian colleges can lose.

Because there are “no great realistic options,” Christian colleges are “having trouble positioning themselves,” Baylor said.

Some are championing Fairness for All, legislation put forward by the CCCU and other faith groups before Trump was elected. Modeled on Utah state law, the legislation would protect religious liberties for institutions while offering civil rights to LGBTQ people.

With cultural pressure increasing, “we have had to build additional bridges and gain additional allies,” Hoogstra said.

“Fairness for All is trying to protect the legitimacy of religious liberty in a way that honors the civil rights of people who think differently,” said Houghton College president and CCCU board vice president Shirley Mullen. Extending protection to LGBTQ people doesn’t mean endorsing their behavior, she said. “As Christian believers we are called to be faithful to what we believe, not to ensure that position is defended by the government.”

Not everyone agrees Fairness for All is the best way forward. Dockery is concerned the bill “trades an unalienable right to religious liberty and makes it a privilege granted by Congress or certain groups within society.” According to Ethics & Religious Liberty Commission president Russell Moore, protecting SOGI in something like Fairness for All “would have harmful unintended consequences and make the situation worse in this country, both in terms of religious freedom and in terms of finding ways for Americans who disagree to work together for the common good.”

Both men—along with about 75 others—signed an opposition statement arguing that SOGI laws “threaten basic freedoms of religion, conscience, speech, and association; violate privacy rights; and expose citizens to significant legal and financial liability for practicing their beliefs in the public square.”

CCCU schools are split on their support for Fairness for All. But “even if some don’t love it, CCCU presidents have told me they understand that the CCCU needs need to be at the table in a legislative space,” Hoogstra said. “We need to get prepared for what will happen when it’s no longer the Trump administration.”

“Basically, any place where a religious college or university depends on the government, either for funding or licenses or accreditation, can become a source of risk if the government decides it doesn’t like your religious beliefs,” Goodrich said.

One of the most obvious pain points is money. Bethel students receive a little more than $3 million a year in Pell Grants and a little more than $4 million a year from state grants. But they receive more than $30 million—a quarter of Bethel’s annual budget—in government loans.

That’s normal. “At CCCU schools, a little under 30 percent of tuition comes through federal loans,” said Bethel chief institutional data and research officer Dan Nelson. At a few schools with lower-income students, that share can be as high as 50 percent.

“As CCCU leaders, we might wish now that we had not earlier on become so dependent on the federal or state government for student grants and loans,” Houghton College president Shirley Mullen said. But for schools with little to no endowments—which describes most Christian colleges—tuition keeps the doors open. And as prices climb, students can’t write the checks without an outside loan.

“We’d have to raise or find an alternative loan source for $150 million to $200 million to replace government loans,” John Brown University president Chip Pollard said. “And then we’d have to raise about $100 million for an endowment we could use to replace $4 million a year in government grants.”

That’s not unprecedented. After a Supreme Court case and Congressional legislation in the ’80s made clear that federal student loans come with Title IX strings, Grove City College and Hillsdale College stopped accepting them.

“After 2000, we made the decision not to accept state funding either,” Hillsdale chief financial officer Patrick Flannery said. (Hillsdale is not a CCCU school.) “It was really difficult, but it helped galvanize us as a campus.”

To cover the federal loans, Hillsdale took out its own loan from a bank, then lent out that money to students. As each class pays it back, the money is lent out to the next class. Grove City also stopped accepting government money, instead partnering with PNC Bank to offer student loans.

But if the Equality Act or a Supreme Court decision expands the definition of sex to include SOGI, no amount of financial distancing would matter. Requiring sexual standards from employees would be straight-up illegal.

Covenant College is taking a serious look at doing the same. “If we have to step away from federal funding, we would,” said Halvorson, who is also on the CCCU board.

Replacing the grants is harder, since it would require a sizable endowment. But the success of Grove City and Hillsdale shows “it’s possible to do,” Halvorson said. “We’re doing everything we can to work ourselves into a position where we could get off federal funding if we needed to.”

It may work—new legislation can tie compliance to funding, and cutting loose would let Christian colleges operate with sexual standards. But if the Equality Act or a Supreme Court decision expands the definition of sex to include SOGI, no amount of financial distancing would matter. Requiring sexual standards from employees would be straight-up illegal.

“I honestly don’t know what we would do if the Equality Act passed,” Bethel president Barnes said. “We have a fairly large board—fully staffed, there are 39 of us—and not everybody thinks in the same direction. It would be a very hard sell for our board to decide [sexual standards] don’t matter anymore. But it would also be really hard for our board to say we’re going out of business.”

Losing the ability to hire in accordance with the institution’s values, or to enforce student codes of conduct, or to accept government funding, would erase much of a Christian college’s distinctiveness. It would be hard to look any different from a secular private university.

Losing the ability to hire in accordance with the institution’s values, or to enforce student codes of conduct, or to accept government funding, would erase much of a Christian college’s distinctiveness.

“You’ll simply have a much larger group of colleges that were once religious,” Houghton’s Mullen said. “And you’ll immediately lose the support of many conservative families.”

But until there is a threat real enough to force decisions, all a board can do is prepare—run the numbers, look into options, call state or federal representatives, campaign against the Equality Act, or evaluate legislation like Fairness for All.

“We’re going around and around,” Barnes said. “If there were an easy answer, we’d have come to it by now. But God is still God, and people who have been faithfully following him have had more difficult things to deal with than this.”

“We often talk about students developing a storm-hardy faith, because sooner or later life gets difficult,” Barnes said. If and when things get difficult for Bethel, he wants the school to lead by example.

“We want our students to believe that when hard things happen, they are not alone,” he said. “God has not forgotten us. He has a way forward for us.”

Halvorson sees the same opportunity.

“We’re concerned first and foremost with being faithful,” he said. “We aren’t going to compromise on clear biblical direction with regard to matters like marriage and sexuality. It’s important for students to see that, and to recognize there may be costs associated with being faithful.”

We aren’t going to compromise on clear biblical direction with regard to matters like marriage and sexuality. It’s important for students to see that, and to recognize there may be costs associated with being faithful.

That doesn’t mean there aren’t “a lot of sleepless nights,” Dockery said. “We want to be as wise and strategic and effective as possible, but ultimately we want to rest our confidence and trust in God’s providence to sustain what we believe is kingdom work. The timing seems right for us to unify, synergize, and strengthen our efforts around our confessional commitments to shared orthodoxy and orthopraxy.”

John Brown University (JBU) has been around for 100 years, Pollard said.

“In 1941 we were under federal bankruptcy supervision, and God preserved us through that,” he said. “We need to be faithful today to what we think we should do in education. . . . I can’t control the future. But I know God will get his work done with or without JBU.”

It’s often because they’re just not ready. They may have grown up in solid Christian homes, been taught the Bible from a young age, and become faithful members of their church youth groups. But are they prepared intellectually ?

New Testament professor Michael Kruger is no stranger to the assault on faith that most young people face when they enter higher education, having experienced an intense period of doubt in his freshman year. In Surviving Religion 101, he draws on years of experience as a biblical scholar to address common objections to the Christian faith: the exclusivity of Christianity, Christian intolerance, homosexuality, hell, the problem of evil, science, miracles, and the Bible’s reliability.

TGC is delighted to offer the ebook version for FREE for a limited time only. It will equip you to engage secular challenges with intellectual honesty, compassion, and confidence—and ultimately graduate college with your faith intact.

Sarah Eekhoff Zylstra is senior writer and faith-and-work editor for The Gospel Coalition. She is also the coauthor of Gospelbound: Living with Resolute Hope in an Anxious Age and editor of Social Sanity in an Insta World. Before that, she wrote for Christianity Today, homeschooled her children, freelanced for a local daily paper, and taught at Trinity Christian College. She earned a BA in English and communication from Dordt University and an MSJ from Medill School of Journalism at Northwestern University. She lives with her husband and two sons in Kansas City, Missouri, where they belong to New City Church. You can reach her at [email protected].